SALLELES D'AUDE Amphoralis GB

My first visit to Amphoralis must have been about 15 years ago, on holiday, I cycled there.

The entrance to the museum is between two great wings, built to protect the remains; you can walk out under these from inside the museum to see what the archeologists found below.

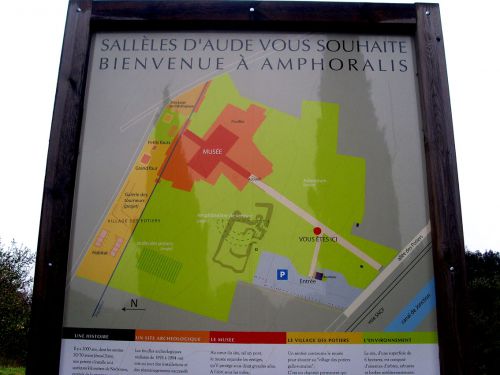

To find Amphoralis from the village, take the road alongside the canal towards Truilhas, and then turn right over the canal where it is sign-posted.

We from the Association Via Aquitana were invited by Les Amis de Clos de la Lombarde to join them on an excursion there in March 2013. We were going to have a guided tour with one of the archeologists, Michel Perron d'Arc, explaining everything.

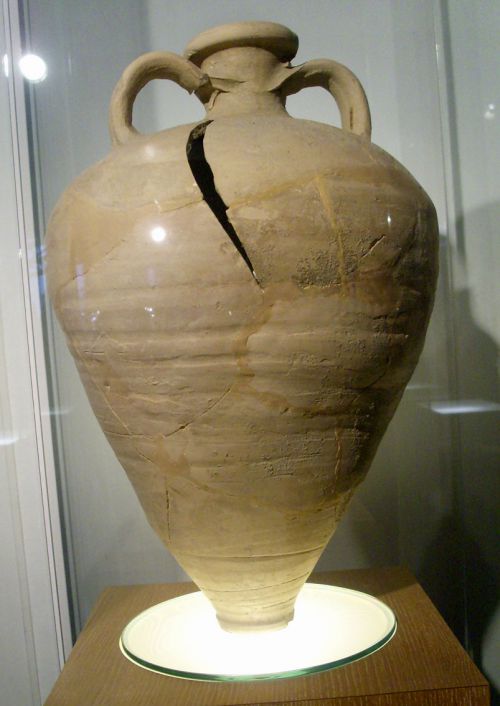

The first display was of amphores.

All made, you notice in the same style, which is in fact unique to Amphoralis, with each amphore having a flat base. Each one contained 26 litres. Their sides were thinner than other aothors, so they were lighter, which helped the wine trade enormously. Sometimes they were packed around with straw in the holds of the boats.

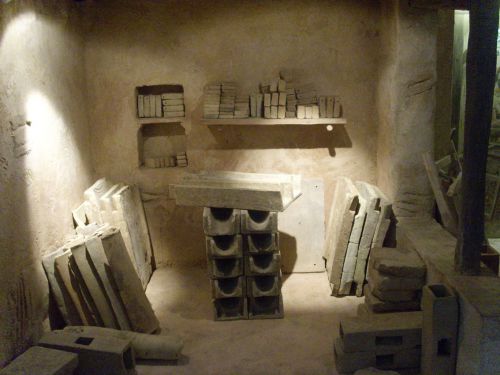

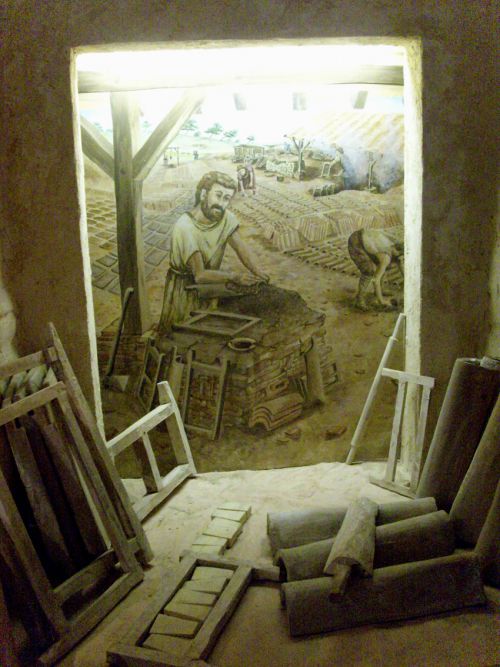

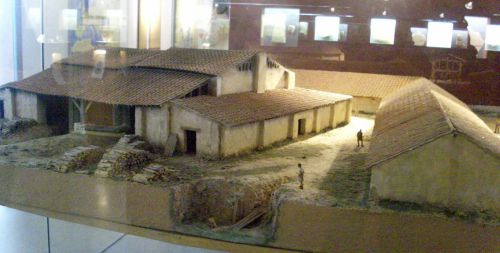

Then we moved to the reconstructions of the workshops.

This was where the clay was shaped. In the first picture you can see the great slabs of rooftiles called tegulae, which were placed side by side with one of the canal tiles over the places where the ridges met. This was quite waterproof. In the room on the left was a potter's wheel. The amphores were made in three parts; the main body up to the widest part, then the neck or col, then the two side handles.

Errors were sometimes made, as you can see from the discarded amphore the archeologists found. The second picture shows how the roof tiles fitted together.

The site of amphoralis was first discovered in 1967 when a local farmer thought his tractor was turning up a lot of broken tiles when he turned the soil. Excavations began to find this was a site of major importance, making clay goods, then firing them into terra cotta in gigantic kilns, that found their way all around the Roman empire. The archeologists in the last fifteen or so years have done many experiments to find out exactly how it was all done and the work arranged. In the years from 30BC to around 300AD, this one site made and exported thousands of amphores.

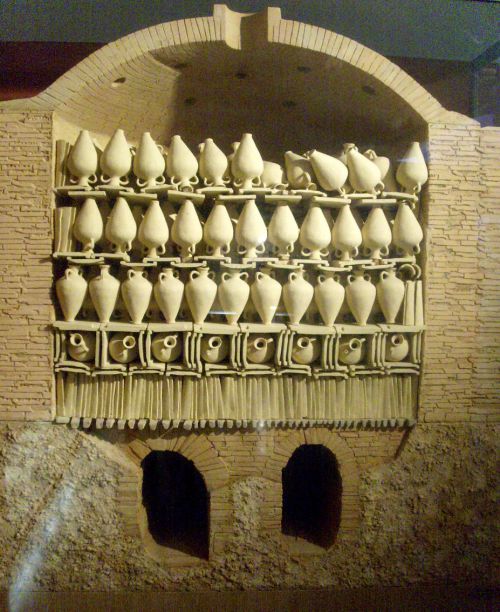

Then we saw reproductions of two of the kilns discovered on the site.

The smaller one had a roof made of small vases, the originals of which can be seen behind it, the larger one was more sophisticated. After the clay was moulded, it was left to dry out for about ten days, according to weather conditions. The fires were lit under the arches, sometimes below ground level, and the heat passed up wards through a floor with small holes in it. Sometimes the heat was a high as 700 degrees. Slow-burning oak was the wood used. The clay was fired for three days, and then the kiln or oven was left to cool down for 15 days. So it took three weeks to manufacture some 350 amphores, in one oven, and there were twelve. As well as amphores, they made rooftiles, small bricks and larger bricks, conduits was water courses, and domestic goods, vases, jugs, bowls and so on, such as the oil-lamp above. And triangular clay weights to be used by weavers.

The kilns were under cover; one can only imagine the immense heat. This was high production industry of Roman times. Many of the workers were slaves who worked between 8 and 10 hours a day, every day. They and their families lived on the site, they were provided with dwellings, they kept domestic animals and grew their own food.

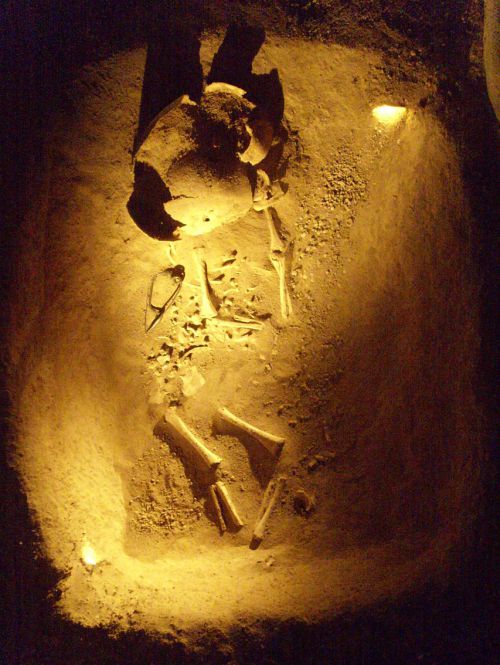

A surprise for the archeologists was the discovery of a small graveyard, containing the graves of 12 infant children, under the beaten floor of one of the dwellings. Some were stillborn, or died at birth, while the oldest was between six and nine months old. Its thought such small children were not considered as people, so they had no funeral rites. But one grave, of a baby about two months, also held a fibula (or safety pin) that would have fastened a shawl the baby was buried in. That doesn't seem to me it was buried by a mother who didn't care for it.

We saw much more in the museum, and went outside to look down over the remains of the ovens.

It was raining when we were there, but there is much to see outside the museum; the house with its garden where the potters lived, the well and the aqueduct that brought water from the river Cesse, and the pit from where they dig the clay.

Inscrivez-vous au site

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 19 autres membres